Management services organizations (“MSO”) have been around for decades serving a multitude of purposes in health care. MSOs colloquially have been referred to as the duct tape for health care business arrangements by health care attorneys. They can fix many problems with a health care deal. When implemented correctly a MSO can be a successful vehicle for several different models, arrangements and reasons. However, if implemented incorrectly a MSO can lead to regulatory scrutiny and risk given the highly regulated health care industry.

This field guide is a five part series and will, after an introduction to the MSO, address in each part the differing uses that MSOs play in health care arrangements:

- Part 1 – What is a management services organization (MSO)?

- Part 2 – Corporate Practice of Medicine (CPOM) Uses

- Part 3 – Regulatory Uses

- Part 4 – Business Structuring Uses

- Part 5 – Exit Plan Uses

Regulatory Uses

An MSO’s use within the Health Care regulatory environment is complex.

On the one hand, the reasoning behind a particular use is many times built upon the same premises and needs described in the other parts of this series. It may be necessary to navigate the corporate practice of medicine (“CPOM”) given the involvement of non-professionals in some capacity with a professional entity. It may be the business structure that best accomplishes the intent of the parties looking to enter into a joint venture.

On the other hand, regardless of need, you must consider and carefully navigate a variety of federal and/or state laws, some of which are highly technical, to ensure the business model can withstand regulatory scrutiny.

Before examining a few examples where MSOs are used in this complex regulatory environment, there are circumstances that should automatically raise a red flag signaling regulatory traps that could lead to potential compliance issues.

Spotting Regulatory Red Flags

Compliance is fact dependent, meaning arrangements must be independently evaluated because changes in facts and circumstances can alter an analysis or conclusion. Avoiding regulatory traps in health care is critically important but takes a lot more information–and good Health Care counsel–to do so effectively.

Consequently, spotting the red flags from the beginning becomes paramount with health care arrangements. Below are three factors to keep in mind to help identify red flags that should signal the need for a more in depth look:

1. Money Involved. The most important place to begin is by identifying the types of payors involved (i.e. who is paying for the service). Where revenue for health care items and services is coming from establishes the laws and rules that come into play, whether directly from patients, insurance companies, Medicare, Medicaid, TRICARE, or other federal Health Care programs (as defined by 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b(f)) (“Federal Programs” and these patients are called “Program Patients”).

2. Patient Referrals are Involved. Most regulations are ultimately designed with the intention to protect patients. Patient referrals to a particular health care provider or facility captures one of the key areas where these regulations come into play. Therefore, any model involving the movement of patients to different providers or facilities can be an indicator of the potential for trouble, particularly if those making referrals have some vested interest in the destination. For example, if a physician refers a patient for lab work and the physician is an owner of the lab, red flags should be raised.

3. Payment for Marketing is Involved. Marketing is a common strategy to disguise patient referrals. As a result, marketing based arrangements are inherently suspect and usually lead to investigation digging deeper beneath the surface to evaluate whether payments for patient referrals are part of the arrangement. These types of arrangements must be approached with caution.

Regulatory Plans

Keeping in mind these factors and knowing the task to spot red flags, the types of regulatory uses of MSOs (both compliant and non-compliant) are next explored. For those so inclined to understand the complexities involved with the regulatory traps, federal and state regulatory laws will be explained in more detail after these uses. What follows are two truths (i.e. compliant) and a lie (i.e. non-compliant) when MSOs and the regulatory environment intersect.

Ancillary Turn-Key Plan (Truth)

The reasoning behind the Ancillary Turn-Key Plan is simple—add an additional service for patients that complements the core services of a health care practice. However, implementation is anything but simple because these complementary services typically require new resources to get started. This is where the MSO comes into play.

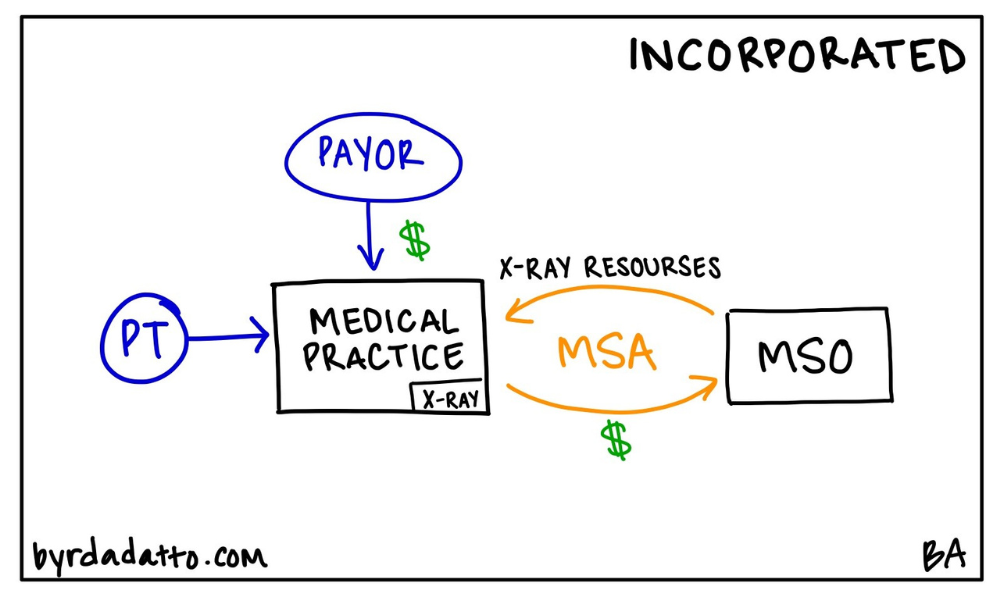

There are typically two ways to think about it. The first way is straight forward–a health care practice looks to add a new service line within the practice. Meaning the service will be performed in-house and billed under the health care practice’s tax id. Thinking about a medical practice, examples include an in-office clinical laboratory, pharmacy, or x-ray room, or offering allergy or other diagnostic services. The Ancillary Turn-Key Plan is found across all different specialties as well as primary care.

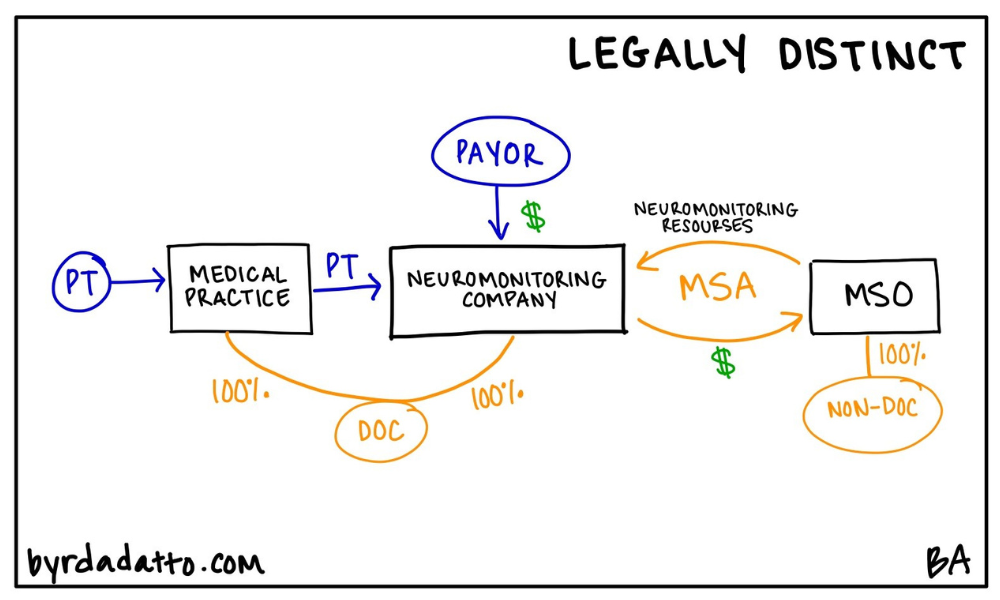

The second way is similar in that a health care practice looks to add a new service line but instead of being incorporated within the practice, a legally separate entity is used. This is more common across surgical specialties and generally focuses on services ancillary to the surgery itself. Rather than being performed in-house, services are typically performed in hospitals or ambulatory surgery centers but could also be performed within in-office surgical suites or facilities. Examples here include intraoperative neuromonitoring or first assist surgical services. Below are illustrations of both models.

In both ways, the MSO plays a key role because it has the resources needed for the ancillary services. Therefore its purpose is to supply the new service line provider (the medical practice or legally separate entity) with the resources needed to start and operate the ancillary service line. These resources can be anything or everything from equipment, personnel, or operational support services. Going back to the basics in Part One of this series, the MSO provides a defined set of non-clinical, administrative services to the health care entity. However, in the Ancillary Turn-Key Plan, it is not uncommon to see substantially all of the work needed to operate the ancillary service line contracted out to the MSO.

What makes the MSO in the Ancillary Turn-Key Plan slightly more unique than when involved in the other uses discussed in this series is the MSO is typically an unrelated third-party vendor specializing in providing the resources. This fact gives rise to specific advantages/disadvantages. While the advantage is that the MSO has everything one needs to get started immediately offering the ancillary service, the disadvantage is then that the health care practice or provider is dependent on the relationship. There is no ability to offer the ancillary service without the MSO and should the relationship end the health care practice or provider is forced to locate a replacement MSO to continue offering the ancillary service line. Yes, a health care practice or provider can create their own MSO or build the ancillary service line in house to maintain control and avoid this issue but the capitalization and learning curve is steep making the Ancillary Turn-Key Plan attractive.

As discussed below, the health care regulatory environment is complex but critical to understand and it’s no different when dealing with the Ancillary Turn-Key Plan. Yet besides considering Stark or the federal anti-kickback statute (“Federal Anti-Kickback”), or state self-referral or anti-kickback laws, one additional aspect to take into account is the Office of Inspector General’s (“OIG”) 2003 Special Advisory Bulletin on Contractual Joint Ventures (“Special Advisory”).

In the Special Advisory, the OIG focused on what it deemed “questionable contractual arrangements” describing the situation where a health care provider expands into a related health care business by contracting with an existing provider to provide the required resources and servicing the health care provider’s existing patient population. The Special Advisory goes on to describe five common elements found in problematic arrangements and an illustrative but not exhaustive, list of suspicious characteristics of these types of deals.

More importantly, the Special Advisory highlighted that “the illegal remuneration is often the difference between the money paid by the [health care provider] to the [related health care business] and the reimbursement received from the federal health care programs.” To the OIG, the “opportunity to generate a fee” by the health care provider is problematic. As you can see, the Ancillary Turn-Key Plan requires careful planning to navigate.

Hospital Co-Management Plan (Truth)

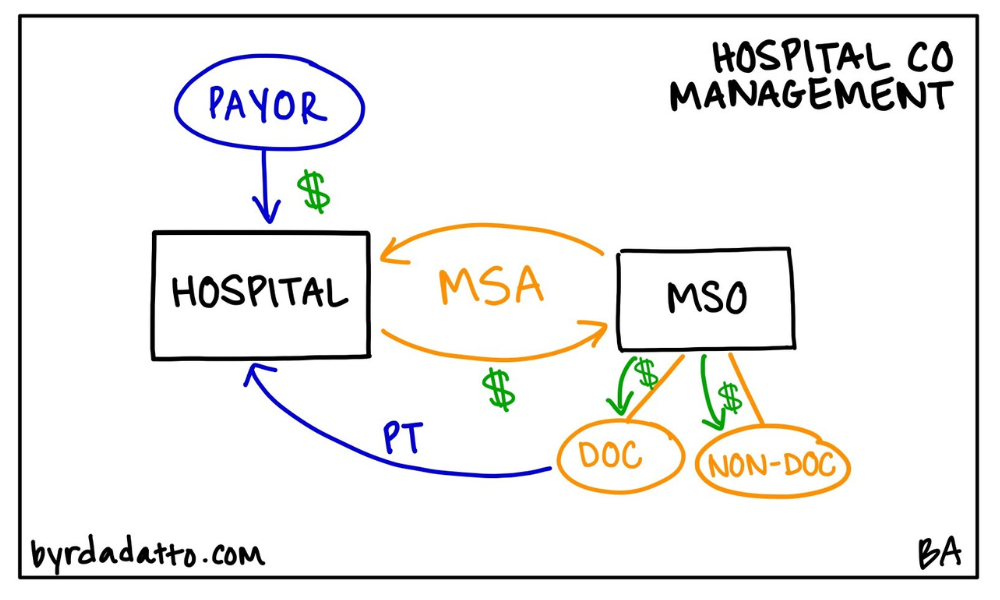

Many times hospitals need help with certain aspects of their clinical operations. This can be specific to a particular hospital department, specialty program, or service line. Who better to help than physicians on medical staff experiencing firsthand the inner workings of the hospital’s clinical operations? That’s where the Hospital Co-Management Plan comes into play—an arrangement where a hospital contracts with an MSO.

What’s important about the Hospital Co-Management Plan (and triggers the complex regulatory rules) is that the MSO is owned by referring physicians and in some cases, a joint venture with both referring physicians and hospital representatives. Below is an illustration of the model.

The most common purpose and function of the MSO in the Hospital Co-Management Plan is to work with the hospital to improve quality and efficiency. To accomplish this, the MSO is tasked, through its physician owners and hospital representatives, to critically look at specific measurable benchmarks and identify ways the hospital can improve performance to meet or exceed the benchmarks. Many times these benchmarks are geared toward the goal of improving the quality of care, reducing hospital costs, or promoting collaboration among various departments or providers.

The compensation from the hospital to the MSO is typically made up of two components: (1) some type of fixed payment associated with the actual work being performed, maybe on an hourly basis; and (2) an incentive bonus tied to the hospital’s performance with respect to the benchmarks.

In preparing to deal with the regulatory traps for the Hospital Co-Management Plan, the same principles apply but typically the compliance risk starts off high because of the presence of Program Patients. This immediately brings into play Stark given the referral of patients for hospital services which are considered designated health services (“DHS”) which as discussed below must first be addressed before moving on to Federal Anti-Kickback considerations.

With the Hospital Co-Management Plan, there are two particular aspects warranting special attention. One is the compensation. With any deal in health care, compensation for services must be set at fair market value, a common element in many Stark exceptions and Federal Anti-Kickback safe harbors (discussed in more detail below). An ancillary consideration to take into account at the beginning is whether all services to be performed are actually necessary and valuable to the hospital as unnecessary services have no particular value, to begin with thereby calling fair market value into question.

While defining and setting fair market value within the context of health care is beyond the scope of this series, the key takeaway is that parties must be able to demonstrate that compensation paid to the MSO is fair market value for the services to be rendered. Most often, especially with the presence of Program Patients, parties obtain a fair market value determination from an independent third party valuation expert. Failing to ensure fair market value compensation can result in compliance issues due to the failure to meet a Stark exception or gain protection of a Federal Anti-Kickback safe harbor.

The second aspect, related to fair market value, is what we refer to as “form and substance,” meaning that the services to be performed by the MSO pursuant to the co-management agreement are actually performed. Because the services are usually personal in nature, it is critical for parties to maintain documentation establishing the actual performance of the contracted services in order to withstand scrutiny.

No matter the model, a critical element is that the substance (what is happening in reality) actually matches the form of the model and corresponding agreements. If parties rely on perfectly developed documents but do not actually operate consistently with their terms and intent, the arrangement will be suspect in the eyes of the regulators.

“Legal Kickback” Plan (Lie)

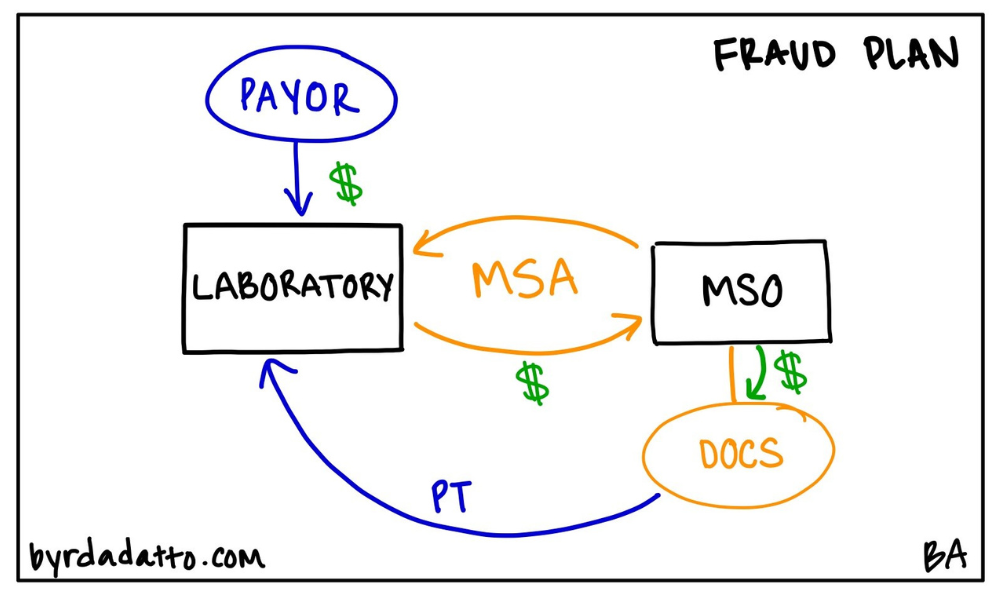

Every seasoned health care attorney likely chuckles at the oxymoron when asked to help with a legal kickback plan as creative minds try to solve for ways to monetize the business (aka patients) that they are sending to a provider. Yet, there is usually some awareness that laws exist prohibiting payment for referrals. These creative minds push boundaries and inquire into how to pay a “legal kickback” (Note to Reader–there is no such thing as a “legal kickback”). The Legal Kickback Plan (again, this is illegal) shows up in health care where, unfortunately, the MSO is used to disguise kickbacks to physicians and other referring providers through investment returns.

The setup appears to be simple and straightforward. An MSO is created to provide services to an ancillary service provider, such as a laboratory or pharmacy. The purported purpose of that MSO many times looks similar to traditional MSO arrangements—it provides certain services to the ancillary service provider and in exchange gets paid a management fee. The next piece is where things go wrong and massive compliance issues arise (as noted because it is illegal).

While the investors in the MSO are referring physicians, similar to the Hospital Co-Management Plan, many times the selection of the investors, the offered ownership opportunity or criteria for investors is directly related to the prospective physicians’ referral patterns to the ancillary service provider being managed. Some models may even require “trial periods” where referring physicians must prove themselves through their referral patterns in order to be granted the opportunity to obtain an investment or to even set how much investment can be acquired. Further, many times there are mechanisms available to force the involuntary relinquishment of ownership when a physician investor fails to make enough referrals.

This direct correlation and relationship to referrals signals a clear intent that the purpose of the arrangement is to compensate physician investors for referrals rather than act as bona fide investment vehicles, which can be done in a compliant way in health care. One requirement though is that referring providers must acquire ownership by paying fair market value. However, in the Legal Kickback Plan, little to no investment is required, yet, distributions become disproportionately great in comparison resulting in significant returns on investments in an extremely short period.

Why is this the case? Form and substance. Going back to the discussion above, whatever services are being required of the MSO must actually be rendered. In the Legal Kickback Plan, typically no services are being provided. Instead, agreements call for nebulous “marketing services” to be rendered but even if an agreement calls for other services, the issue arises from the fact that the MSO typically has no resources or ability to actually render the services because it is a shell entity. Some models attempt to address this particular issue by subcontracting out the services to be performed by yet another entity. However, this approach fails in that it calls into question the need for the MSO owned by the referring physician and doesn’t solve the issue of it being a shell entity.

Below is an illustration of the Legal Kickback Plan.

While the Legal Kickback Plan on its face appears to resemble other traditional MSO models, going through the regulatory compliance aspects brings to light that there are significant differences. And the OIG has taken notice.

There have been several settlements, an example being on June 28, 2022, with 15 doctors in Texas, stemming from alleged violations of the Federal Anti-Kickback and Stark for receiving money from nine MSOs in exchange for ordering laboratory tests from Rockdale Hospital dba Little River Health Care, True Health Diagnostics LLC, and Boston Heart Diagnostics Corporation. The MSO was allegedly used to pay these physicians for their referrals where the payments were labeled as investment returns. This is just one example of the proliferation of the use of the MSO and the creation of the Legal Kickback Plan.

Regulatory Traps

As noted in the first two parts of this series, MSOs can be utilized as a benefit to physicians and non-physicians alike. However, like many aspects of the health care industry, these models are subject to intense scrutiny and parties should cautiously enter into such arrangements ensuring they meet applicable federal and state rules.

Federal Laws

When an arrangement involves Federal Programs, not only do the federal laws, rules, and regulations come into play but also the Federal Government’s significant enforcement history whether it’s the OIG, Department of Justice (DOJ), Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI), or Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS). Fortunately, well-developed guidance for compliance exists through the publication of regulations, issued advisory opinions, and case law. While the two most commonly triggered federal laws in this area are discussed in detail below, other laws could be involved, such as the Eliminating Kickbacks in Recovery Act of 2018 and Physician Payment Sunshine Act.

Any federal law analysis begins with the Stark law. Stark is the federal physician self-referral prohibition. Found in Section 1877 of the Social Security Act (42 U.S.C. 1395nn), Stark is a civil statute where penalties include fines as well as exclusion from participation in Federal Programs. Stark may be broken down into the following components:

- It applies to physicians – “Physician” is a defined term only including doctors of medicine or osteopathy, dental surgery or dental medicine, podiatric medicine, optometry, and chiropractors. This means Stark does not apply to nurse practitioners, physician assistants, registered nurses, any other licensed professional, or unlicensed individuals.

- It prevents physicians from making referrals for DHS – DHS are specific types of services that include among others, clinical laboratory services, inpatient and outpatient hospital services, radiology and certain other imaging services, durable medical equipment, and outpatient prescription services.

- It applies to referrals for DHS payable by Medicare or Medicaid – Stark only applies if referrals involve patients covered by Medicare or Medicaid (in whole or in part, and whether as a primary or secondary payer). Therefore when no Medicare or Medicaid patients are involved, Stark will not apply.

- The referrals are to entities with whom the physician (or an immediate family member) has a financial relationship – Financial relationships can be direct or indirect ownership, investment interests, or compensation arrangements.

Stark is typically thought of as a bright-line rule because one either violates Stark or not. Moreover, Stark has exceptions to the general prohibition but again all of the requirements of a specific exception for an arrangement must be met to be permitted. Failure to meet one element of an exception means the arrangement violates Stark (unless another exception applies). Any regulatory analysis must begin here because of this bright line you either meet it or you don’t rule.

Next, Federal Anti-Kickback (42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b(b)) is a criminal law with criminal penalties and administrative sanctions for violations including fines, jail terms, and exclusion from participation in the Federal Programs. Broken down into components:

- It applies to any person – unlike Stark that only applies to “physicians,” Federal Anti-Kickback applies to all sources of referrals, including patients.

- It prohibits any person from knowingly and willfully soliciting, receiving, offering, or paying any remuneration directly or indirectly, overtly or covertly, in cash or in kind -Remuneration includes any kickback, bribe, or rebate but remuneration is more than just payment of funds and has been interpreted to be anything of value.

- Remuneration can’t be in return for or to induce a person to do either of the following:

- Refer an individual to a person for the furnishing or arranging for the furnishing of an item or service for which payment may be made in whole or in part under any Federal Program; or

- Purchase, lease, order, or arrange for or recommend the purchasing, leasing, or ordering of any good, facility, service, or item for which payment may be made in whole or in part under any Federal Program.

Within the Federal Anti-Kickback, “safe harbors” exist to protect arrangements. To meet a safe harbor, one must satisfy every element to be guaranteed protection from a violation. However, unlike Stark’s bright line nature, failure of an arrangement to meet every element of a safe harbor does not make the arrangement automatically illegal. Instead, the failure means the arrangement is scrutinized without protection of the safe harbor.

What makes the Federal Anti-Kickback particularly difficult to navigate is not just the language of the statute but also the fact that it is broadly interpreted to cover any arrangement where one purpose of the remuneration is to obtain money for the referral of services or to induce further referrals. This broadness means the Federal Anti-Kickback must be considered when any arrangement or model involves patients covered by Federal Programs.

State Laws

The regulatory floor will always be state laws, rules, and regulations regardless of the payors involved.

Even if federal laws won’t directly apply, state laws can point to, mirror, or follow their federal counterpart. In addition, unlike the federal laws, state laws typically are not as actively enforced publicly, nor do they have as much developed guidance for compliance. This means the federal laws and their guidance can be helpful for determining compliance with state laws.

Even in a state with no enforcement activity, the laws must still be taken into account because violations can be relied upon by third parties such as licensing boards, insurance payors, and even contracting parties.

Just as with CPOM, each state’s laws will be unique. Yet, the same types of prohibitions are generally considered in some way. Self-referral prohibitions may exist dealing with the referral of a patient by a provider to a separate business where they have a financial interest. More states have some form of state law, rule, or regulation prohibiting payments for referrals. State bribery statutes include not only those prohibiting commercial bribery, but may also address illegal remuneration regarding improper payments in connection with referrals for services.

Where differences really come to light is in the way the laws actually become applicable. They may apply to a limited set of payor sources (i.e. state Medicaid programs) or be payor indifferent (doesn’t matter who makes the payment, even cash). They could apply to a limited set of health care services (i.e. designated health services) or apply to any health care service being referred. Once again since self-referral laws tend to be more bright line rules similar to Stark, any state level analysis should begin there.

Other Rules

Licensing boards establish rules that many times contain a laundry list of actions the board deems to be unprofessional conduct. Sometimes the list includes specific prohibitions, including prohibitions on self-referrals and kickbacks, but other times it may include general references to incorporate violations of federal and state laws.

Ethical rules established by associations or professional societies create risk as well. For example, the American Medical Association has a specific Code of Ethics Opinion stating flatly that payment by or to a physician or health care institution solely for referral of a patient is fee splitting and is unethical. Other examples of potentially applicable codes of ethics include the Advanced Medical Technology Association (AdvaMed) and the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS).

Contact ByrdAdatto

At this point, it should be clear the MSO’s use within the health care regulatory environment is complex. Navigating complex laws, making sure form and substance match, and combating the pull to find “legal kickbacks” are traps that can snare anyone unprepared. Successful MSOs not only identify red flags from the beginning but also carefully analyze the situation in the context of all of the applicable laws to ensure compliance.

In Part Four of this series, we will discuss the next use for MSOs – business structuring. If you have any questions or would like to learn more about MSOs, email us at info@byrdadatto.com.